This article originally appeared in Hill Times Research on April 21, 2022.

Two pharma industry advocates say they’re encouraged by Health Canada’s recent announcement that it will go ahead with only one of three regulatory changes meant to reduce patented drug prices.

“We’re encouraged at that step forward and look forward to working with governments on any number of other files,” said Pamela Fralick, president of Innovative Medicines Canada (IMC).

“I think it’s an important recognition of how complex this issue is. I find it encouraging that the government … understands that it’s not only just to look at things through a very narrow pricing prism,” said Andrew Casey, president and CEO of BIOTECanada. (Both Fralick and Casey spoke to Hill Times Research by phone on April 20.)

Casey attributed that “recognition” in part to the pandemic, which resulted in the federal government collaborating with the industry in its efforts to produce vaccines and therapeutics for COVID-19.

Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos (Québec, Que.) alluded to that collaboration in his April 14 statement about the government’s changed plans for the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board’s (PMPRB) drug pricing regulatory reviews.

Since the regulatory amendments were first proposed, “the pharmaceutical landscape has shifted dramatically, a new context has developed brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the progression of various initiatives seeking to improve accessibility and affordability for needed medicines,” Duclos said.

The federal Liberals announced their plan to change the PMPRB’s pricing review process in 2017, and published the final regulations in Canada Gazette II in 2019. After five years of tension between the government and the pharmaceutical industry, and multiple legal challenges on the matter, Duclos said in the press release that the government would only move forward with one of three changes designed to reduce prices when the regulations go into effect on July 1, 2022.

Change comes in a basket

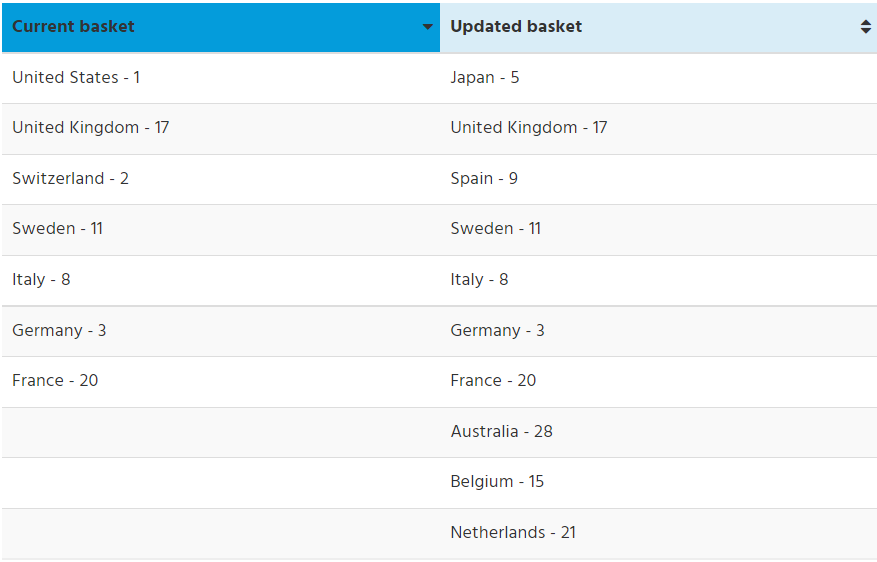

Letting go of a plan to introduce new economic factors to the regulatory review and requiring pharmaceutical companies to disclose their third-party pricing agreements with public and private insurers, the Liberals will move forward with an update to the list (or basket) of countries used by the PMPRB to learn what other jurisdictions are paying for the same medicines that are entering the Canadian market. The new list eliminates two jurisdictions – the United States and Switzerland – where drug prices are highest in the world, and adds six new countries to the list, with a focus on jurisdictions that pay less than Canada for medicines.

Of the three components, the basket of countries was the only pre-2017 measure used by the PMPRB in their regulatory reviews. It is also the only measure to survive a Quebec Court of Appeal ruling issued on Feb. 18, 2022. The case was brought forward by multiple pharmaceutical companies, including Merck Canada and Janssen Canada, who were challenging the government’s ability to introduce the updated basket of countries and economic factors. A requirement to disclose third-party agreements was struck down in a Quebec Superior Court ruling on Dec. 18, 2020. (BIOTECanada was an intervenor in the case that took place before the Quebec Superior Court, but not the appeal of that decision.)

There is a second court case playing out at the Federal Court of Appeal, with IMC being one of the multiple appellants waiting for a decision on their appeal of a Federal Court ruling issued on June 29, 2020. The Federal Court, like the Quebec Superior Court’s decision, stated the government could go ahead with the updated basket of countries and the economic factors but quashed the ability to demand third-party pricing agreements.

Little power in regulating by basket alone, says academic

The government’s decision to eliminate two of the three measures was “disappointing but not unexpected,” said Dr. Steve Morgan, a pharmacare expert and advocate who teaches at the University of British Columbia.

The decision wasn’t that surprising considering the strong opposition of the industry and other pharma-funded groups, and the court rulings against the government, but it was disappointing that the government did not try to appeal the most recent ruling to the Supreme Court, said Morgan.

He called the economic factors and third-party pricing disclosure element the innovative parts of the regulations, saying that Canada was in a sense leading the world in terms of pharmaceutical policy.

“There has been quite a bit of dialogue in the last six or so years internationally … about that kind of regulatory framework and Canada was essentially going to be the first which probably explains some of the opposition that we faced,” he said.

Maintaining the basket of countries, even in its updated form, is keeping the status quo, according to Morgan.

The prices that are available through the basket are list prices, and not what governments and insurance companies usually pay for medicines. The rebated prices paid by those third parties are set after confidential negotiations and are typically lower than list prices.

“When you know that all organized purchasers in other countries are negotiating deals that can be 20, 30, 50, even 70 per cent off of the list price, well, then just regulating the list price doesn’t particularly provide you much useful regulatory power,” Morgan said. His own research of rebated drug prices in high-income countries, including Canada, indicates that a discount of 20 to 30 per cent is typical, but it can go as high as 50 or 60 per cent.

Although IMC is encouraged by the government’s intention to avoid most of the regulatory changes, it is still concerned about the use of the updated basket of countries, which it made clear in an April 20 statement reacting to Duclos’s announcement. Fralick is quoted as saying that the updated list “does little to cultivate the competitive market needed to attract global investment and to ensure access to the best medicines for Canadians.”

Expanding on those concerns in her Hill Times Research interview, Fralick said the statement is meant to raise the question of whether it makes sense to add countries belonging to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development that are on the “median” level when Canada is a “higher-level OECD country.”

“We know that we all want to do everything possible to make sure that this global industry does, in fact, see Canada as that attractive place to invest in … We want the government again to reflect on the basket and the implications on other aspects of the life sciences sector,” Fralick said.

On the Federal Court of Appeal’s pending decision, Fralick said her organization has not yet made any decisions on future legal steps, and that it has to consult with its legal counsel and members.

BIOTECanada’s Casey said that using the basket as a comparative tool makes sense and that the countries included in the updated basket have similar economies to Canada.

“Just make sure that you’re not looking to drive prices down to the lowest part of that grouping, but you want to make sure you’re competitive with all countries that are trying, just like us, to attract investment from the industry,” Casey said.

Reducing drug costs for Canadians is still on the federal government’s agenda and will likely be required if the minority Liberal government wants to survive until 2025. In a confidence and supply agreement reached by the Liberals and the NDP, the government promised to pass legislation for a national pharmacare program by the end of 2023, in exchange for the NDP’s support on matters of confidence.

How can Canada reduce drug prices?

Morgan’s view is that if the government is serious about implementing pharmacare and lowering drug prices, then it has to implement a single-payer pharmacare program that will see a single entity negotiate rebated drug prices on behalf of the entire country.

Currently, the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA), consisting of representatives from provincial, territorial, and federal governments, negotiate collectively with pharma companies to include new medicines on their public formularies. Private insurance providers conduct their own negotiations for medicines covered by workplace benefits plans.

Having a single negotiator means “you will end up with the purchasing power of nearly 40 million Canadians,” Morgan said. “That power should be sufficient to make sure that the prices that that system negotiates will represent fair value for money … Otherwise, that system will say no to a manufacturer and say that [the manufacturer is] going to have to come back with a better deal.”

When asked what the industry’s solution would be to reduce drug prices, Fralick said that it would like to move forward on “innovative models for financing.”

“[That] is something that is drawn from our global experience. We often talk about the fact that other countries are doing all these interesting things. Let’s learn from them,” she said.

IMC, in collaboration with BIOTECanada, published a paper last October describing five models that would be described as innovative financing. One model is called a performance-based pricing agreement which would have the negotiating parties set the price based on the level of clinical benefit achieved by patients. Another model is labelled an “amortization” agreement in which payments occur over a specified period of time, with one benefit cited as making an innovative drug immediately available but not having the total cost tied to a single budget cycle.

Casey said there are already two effective tools being used to reduce drug prices in Canada in the form of the pCPA and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, which conducts health technology assessments for the purpose of recommending to provincial and territorial formularies (with the exception of Quebec) whether they should fund a new medicine. That recommendation involves studying the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a new drug approved for use in Canada.